Understanding Alzheimer’s Disease: A Guide to Its Causes and Risk Factors

Alzheimer’s disease stands as the most common cause of dementia, a relentless condition that gradually erodes memory, thinking skills, and the ability to carry out the simplest tasks. For millions of families worldwide, it represents a profound personal challenge. While a definitive cure remains elusive, decades of scientific research have illuminated the complex biological mechanisms and risk factors that drive this neurodegenerative disorder. Understanding what causes Alzheimer’s disease is the critical first step toward prevention, earlier diagnosis, and the development of more effective treatments.

The Hallmark Pathologies: Amyloid Plaques and Tau Tangles

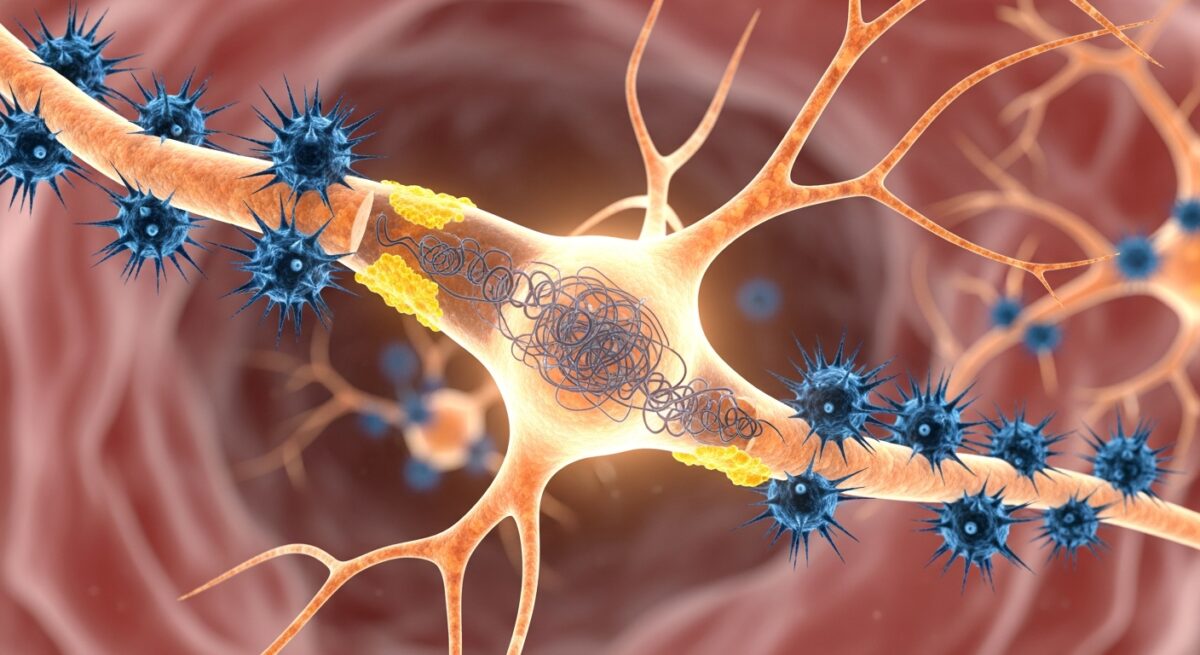

At its core, Alzheimer’s disease is defined by two abnormal protein structures that accumulate in the brain: amyloid plaques and neurofibrillary tangles. These are not merely byproducts of the disease, they are believed to be central players in the neuronal damage and cell death that characterize Alzheimer’s. The amyloid hypothesis, a leading theory for decades, posits that the disease process begins with the improper processing of a protein called amyloid precursor protein (APP). Normally, APP is cut into smaller fragments that are harmless and cleared away. In Alzheimer’s, however, it is cleaved in a way that produces sticky fragments called beta-amyloid peptides.

These beta-amyloid fragments clump together outside neurons, forming dense, insoluble deposits known as amyloid plaques. These plaques are thought to disrupt communication between nerve cells (synapses) and may trigger inflammatory responses that damage surrounding brain tissue. Importantly, plaques can begin to form decades before any symptoms of memory loss appear. The second key pathology involves a protein called tau. Inside healthy neurons, tau proteins help stabilize internal structures called microtubules, which act like railroad tracks for transporting nutrients. In Alzheimer’s, tau proteins become chemically altered, detach from the microtubules, and stick to other tau threads. They form twisted fibers known as neurofibrillary tangles inside the cell bodies of neurons.

These tangles block the neuron’s transport system, leading to a failure in communication and, ultimately, cell death. The spread of tau tangles through the brain closely correlates with the progression of cognitive decline. While plaques and tangles are the defining features, their exact relationship and which is the primary driver is still a subject of intense research. Most scientists now believe they work in a synergistic, toxic partnership to dismantle brain function.

Genetic Factors and Familial Risk

Genetics play a significant but complex role in Alzheimer’s disease risk. Researchers categorize this risk into two groups: deterministic genes and risk genes. Deterministic genes are rare and directly cause a form of the disease known as early-onset or familial Alzheimer’s disease, which typically strikes before age 65. Mutations in three genes (APP, PSEN1, and PSEN2) are known to cause this inherited form, accounting for less than 1% of all cases. If a parent carries one of these mutations, a child has a 50% chance of inheriting it and almost certainly developing the disease.

For the vast majority of cases, which are late-onset Alzheimer’s (symptoms appearing at 65 or older), genetics influence risk rather than guarantee the outcome. The most significant known genetic risk factor is the apolipoprotein E (APOE) gene on chromosome 19. Everyone inherits one form of the APOE gene from each parent. The APOE ε4 allele increases risk and may lower the age of onset. Having one copy increases risk, while two copies (one from each parent) increases risk even more. However, it is crucial to understand that carrying APOE ε4 does not mean a person will definitely develop Alzheimer’s, and many people with the disease do not have this allele. Other risk genes have been identified through large genome-wide studies, each contributing a small increase in overall susceptibility.

Modifiable Risk Factors and Lifestyle Influences

While age and genetics are factors we cannot change, a growing body of evidence points to several modifiable risk factors. These are lifestyle and health conditions that, if managed, could potentially delay the onset or reduce the overall risk of developing Alzheimer’s disease. The brain’s health is deeply connected to the health of the heart and blood vessels. Conditions that damage the cardiovascular system can also impair blood flow to the brain. Key cardiovascular risk factors include:

- Hypertension (high blood pressure), especially in midlife.

- Diabetes and insulin resistance, which can impair brain cell energy metabolism.

- High cholesterol, which may influence amyloid deposition.

- Obesity, particularly in middle age.

Chronic inflammation, whether from long-term infections, autoimmune conditions, or lifestyle factors like poor diet, is another area of focus. The brain’s immune cells, called microglia, may become dysregulated, contributing to neuronal damage. A sedentary lifestyle lacks the cognitive stimulation and social engagement that help build and maintain cognitive reserve, the brain’s resilience to pathology. Conversely, lifelong learning, complex mental activities, and strong social networks are associated with a lower risk. Traumatic brain injury (TBI), particularly repeated concussions, is a well-established risk factor. TBI can trigger processes that accelerate the accumulation of tau tangles.

The Role of Age, Inflammation, and Cellular Processes

Advancing age is the single greatest risk factor for Alzheimer’s disease. The risk doubles about every five years after age 65. The aging brain undergoes numerous changes: reduced energy production in cells, increased oxidative stress from free radicals, diminished ability to clear damaged proteins (a process called autophagy), and a decline in the efficiency of synapses. These age-related vulnerabilities create a fertile ground for the pathologies of Alzheimer’s to take hold and progress. Neuroinflammation, once thought to be merely a consequence of plaque and tangle formation, is now recognized as an active and potentially driving component of the disease.

The brain’s resident immune cells, microglia, attempt to clear amyloid plaques and cellular debris. In Alzheimer’s, this inflammatory response can become chronic and destructive, releasing chemicals that harm neurons. Mitochondria, the power plants of cells, also malfunction in Alzheimer’s. Neurons are energy-intensive cells, and mitochondrial dysfunction leads to a critical energy deficit, oxidative stress, and can trigger cell death pathways. For a deeper dive into how age-related health policies intersect with managing such conditions, you can Read full article on resources for seniors.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can Alzheimer’s disease be prevented? There is no proven way to prevent Alzheimer’s, but strong evidence suggests that managing cardiovascular risk factors (like hypertension and diabetes), engaging in regular physical and mental exercise, maintaining a healthy diet (such as the Mediterranean or MIND diets), fostering social connections, and getting quality sleep may help reduce risk or delay onset.

Is Alzheimer’s disease hereditary? In the rare early-onset form (before 65), it can be strongly inherited through specific gene mutations. For the more common late-onset form, having a first-degree relative with the disease increases one’s risk, but it is not a simple hereditary pattern. It involves a combination of genetic susceptibility (like the APOE ε4 gene) and environmental/lifestyle factors.

What is the difference between normal aging forgetfulness and Alzheimer’s? Normal age-related memory changes might include occasionally forgetting names or appointments but remembering them later. Alzheimer’s-related memory loss is more persistent and disruptive to daily life, such as forgetting recently learned information, important dates, or events, and asking for the same information repeatedly.

How is Alzheimer’s disease diagnosed? There is no single test. Diagnosis involves a comprehensive assessment including a detailed medical history, mental status testing, neurological and physical exams, and brain imaging (like MRI or PET scans) to rule out other conditions and look for patterns of brain changes. Newer blood tests for biomarkers like p-tau are becoming available to aid diagnosis.

Unraveling the causes of Alzheimer’s disease reveals a multifaceted picture where genetics, biology, aging, and lifestyle intersect. It is a puzzle with many pieces, from the microscopic misfolding of proteins to the broad impacts of heart health and social engagement. While the complexity can feel daunting, each discovery provides a new potential target for intervention. This understanding empowers individuals to take proactive steps for brain health and fuels the global scientific pursuit of effective therapies. Continuing to support research and raising awareness remains our most powerful tool in the fight against this disease.