Defining Alzheimer’s: Understanding Its Nature as a Disease

When a loved one starts forgetting important dates, repeating questions, or struggling with familiar tasks, a single, frightening word often emerges: Alzheimer’s. But what exactly is Alzheimer’s? Is Alzheimer’s a disease, a natural part of aging, or something else entirely? This question is more than semantic. It shapes how we fund research, provide care, and support the millions of individuals and families navigating this condition. At its core, Alzheimer’s is definitively classified as a progressive, degenerative brain disease. It is the most common cause of dementia, a general term for a decline in cognitive ability severe enough to interfere with daily life. Understanding it as a disease is the first critical step toward effective management, treatment, and, ultimately, hope for a cure.

The Scientific Consensus: Alzheimer’s as a Brain Disease

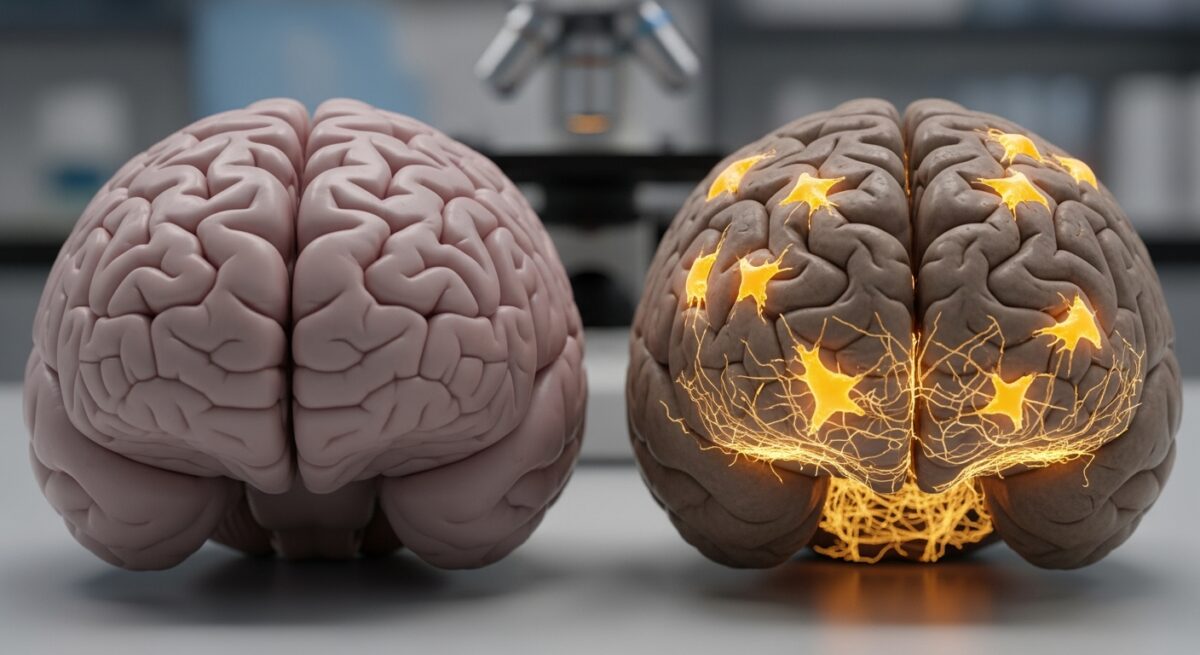

The medical and scientific communities worldwide classify Alzheimer’s as a disease. This classification is based on decades of pathological evidence showing distinct, abnormal physical changes in the brains of affected individuals. These changes are not a normal or inevitable consequence of aging. A healthy aging brain may experience some slowing of recall or processing speed, but it does not experience the widespread neuronal death and tissue loss characteristic of Alzheimer’s disease.

The hallmarks of Alzheimer’s disease are two abnormal protein structures: amyloid plaques and neurofibrillary tangles. Amyloid plaques are clumps of a protein fragment called beta-amyloid that build up in the spaces between nerve cells. Neurofibrillary tangles are twisted fibers of a protein called tau that accumulate inside brain cells. Scientists believe these formations disrupt communication between neurons, inhibit cellular transport systems, and trigger inflammation, eventually leading to cell death. This process begins in regions of the brain crucial for memory, like the hippocampus, and gradually spreads to other areas, affecting language, reasoning, and social behavior. This biological origin story firmly places Alzheimer’s in the category of a physical disease, not a psychological state or simple forgetfulness.

Dementia vs. Alzheimer’s: Clarifying the Terminology

A common point of confusion is the difference between dementia and Alzheimer’s disease. Dementia is not a specific disease, it is an umbrella term for a set of symptoms. Think of dementia as a syndrome, like “fever.” A fever is a symptom with many possible causes, such as the flu or an infection. Similarly, dementia describes symptoms including memory loss, impaired judgment, and personality changes. Alzheimer’s disease is the most common cause of the dementia syndrome, accounting for an estimated 60-80% of cases.

Other diseases can also cause dementia. These include vascular dementia (often after a stroke), Lewy body dementia, frontotemporal dementia, and dementia due to Parkinson’s disease. Each has different underlying pathologies and, in some cases, different symptom patterns. Therefore, while all Alzheimer’s patients experience dementia, not all dementia is caused by Alzheimer’s. A proper diagnosis by a healthcare professional is essential to identify the specific disease process at work, which guides treatment and management strategies. For a deeper exploration of related conditions and care options, you can Read full article on our dedicated resource page.

Why the Disease Designation Matters: Implications and Impact

Labeling Alzheimer’s as a disease has profound practical and societal implications. It moves the condition out of the shadow of stigma and misconception, where cognitive decline was once dismissed as “senility” or an unavoidable fate. Recognizing it as a disease validates the experience of patients and families, framing it as a medical condition requiring medical attention, research, and compassionate care.

This designation directly impacts several key areas. First, it drives research funding. Diseases are studied in laboratories and clinical trials. The classification of Alzheimer’s as a disease has mobilized billions of dollars in research from governments and private organizations worldwide to understand its mechanisms and develop treatments. Second, it shapes healthcare systems. Disease status influences insurance coverage, eligibility for disability benefits, and the development of specialized care pathways. Third, it affects public perception and advocacy. A defined disease can be campaigned against, leading to greater public awareness, reduced stigma, and stronger support networks. It shifts the narrative from one of passive decline to one of active management and the pursuit of cures.

Dispelling Myths: Alzheimer’s Is Not Normal Aging

A persistent and harmful myth is that Alzheimer’s is just a severe form of normal aging. This misconception can delay diagnosis and treatment, as families may chalk up early symptoms to “just getting old.” It is crucial to distinguish between age-related memory changes and signs of disease.

Normal age-related changes might include occasionally misplacing keys, momentarily forgetting a name but recalling it later, or sometimes needing help with a new technology. These do not dramatically interfere with a person’s ability to live independently. In contrast, the memory loss associated with Alzheimer’s disease is disruptive and progressive. It often involves forgetting recently learned information, important dates or events, asking the same questions repeatedly, and increasingly needing to rely on memory aids or family members for things they used to handle on their own. Beyond memory, Alzheimer’s affects reasoning, visual-spatial relationships, and the ability to complete multi-step tasks like managing finances or following a recipe.

Understanding the key differences can empower individuals to seek early evaluation. Early diagnosis allows for better management of symptoms, access to medications that may help for a time, and the opportunity to participate in clinical trials. It also gives the individual and their family time to plan for the future, make legal and financial arrangements, and consider care preferences.

Risk Factors, Causes, and the Path to Treatment

While the exact cause of Alzheimer’s is not fully understood, it is believed to result from a combination of genetic, lifestyle, and environmental factors that affect the brain over decades. Age is the greatest known risk factor. The likelihood of developing Alzheimer’s doubles about every five years after age 65. Family history and genetics also play a role, with specific genes like APOE-e4 increasing risk. However, having a risk gene does not guarantee someone will develop the disease, and many people with Alzheimer’s have no family history.

Researchers are actively investigating other contributing factors, including heart health (the health of your heart and blood vessels directly impacts your brain), head trauma, and overall healthy aging. The current understanding suggests that interventions promoting general health may help reduce risk or delay onset. These include managing cardiovascular risk factors like hypertension and diabetes, staying physically and socially active, engaging in mentally stimulating activities, and maintaining a healthy diet. While there is no surefire way to prevent Alzheimer’s, these lifestyle choices support overall brain health.

Treatment for Alzheimer’s disease currently focuses on two main areas. First, medications can help manage cognitive symptoms. These include cholinesterase inhibitors and memantine, which work on brain chemistry to help with memory, thinking, and behavior for a limited time. Second, non-drug approaches are vital. Creating a safe and supportive environment, managing behavioral symptoms, and providing caregiver education and support are all essential components of care. The ultimate goal of research is to find disease-modifying therapies that can slow or stop the progression of the disease itself, not just manage symptoms.

Frequently Asked Questions

Is Alzheimer’s disease hereditary?

Most cases of Alzheimer’s are not directly inherited in a simple pattern. However, having a first-degree relative with the disease increases your risk. A very small percentage of cases, known as early-onset familial Alzheimer’s, are caused by specific genetic mutations and are strongly inherited.

Can you die from Alzheimer’s disease?

Yes. Alzheimer’s is a fatal disease. It is the sixth-leading cause of death in the United States. The brain damage it causes leads to a decline in bodily functions, complications like infections (e.g., pneumonia), and ultimately death.

What are the very early signs?

Early signs often extend beyond simple forgetfulness. They may include challenges in planning or solving problems, difficulty completing familiar tasks, confusion with time or place, trouble understanding visual images, new problems with words in speaking or writing, misplacing things and losing the ability to retrace steps, decreased or poor judgment, withdrawal from work or social activities, and changes in mood and personality.

How is Alzheimer’s disease diagnosed?

There is no single test. Diagnosis involves a comprehensive medical evaluation, including a detailed medical history, mental status testing, physical and neurological exams, and tests (like blood work and brain imaging) to rule out other possible causes of dementia symptoms.

Is there a cure for Alzheimer’s?

Currently, there is no cure for Alzheimer’s disease. Available treatments can temporarily slow the worsening of symptoms and improve quality of life, but they do not stop or reverse the underlying disease process. This reality underscores the critical importance of continued research.

Understanding Alzheimer’s as a progressive brain disease is fundamental. It provides a framework for compassion, a mandate for scientific pursuit, and a call to action for better support systems. While the journey with Alzheimer’s is undeniably challenging, accurate knowledge empowers individuals, families, and communities to face it with greater clarity, seek appropriate resources, and advocate for a future where effective treatments and prevention are a reality. The path forward is built on research, care, and the unwavering commitment to improving lives.